Posts tagged ‘community gardens’

Harvesting Garden History, One Story at a Time

The Joseph Daniel Wilson Memorial Garden in New York City.

October is Archives Month, and as gardeners across the country harvest the last of their summer crops, we’re turning our attention to a different type of harvesting: preserving stories about gardens for future generations. Smithsonian Gardens’ Community of Gardens digital archive is celebrating Archives Month with a story-behind-the-story featuring a contributor to our digital archive.

Elizabeth Eggimann is an independent researcher in storytelling and landscape history. During her senior year at Pace University in New York City, she set out to document the untold stories of the community gardeners who have shaped the urban landscape of New York City. Tucked into formerly vacant lots and pockets of green between alleys and asphalt, these nook-and-cranny gardens are vibrant hubs of community energy and activism. Eggimann chose to interview a handful of current community gardeners rather than focus on an all-encompassing narrative of the complex history of urban community gardening in New York City. Their thoughts and wisdom form a snapshot of a city that is ever-changing in the face of development. Eggimann stresses that these oral histories were in many ways a collaborative endeavor. “The narrators are the authors of their stories,” she explains, “without their contribution, time, and generosity this project would not have been possible.”

We asked her to share her thoughts on the experience of embarking on an oral history project spotlighting gardens and gardeners. A few of the stories from her research are featured in the Community of Gardens digital archive.

How did you first become interested in community gardens?

I first became interested in community gardens when I lived adjacent to a garden in New York City’s East Village. A window in my room looked down into the garden space, which, to my delight, offered fantastic bird watching. I slowly began spending more time in the garden—having my morning cup of coffee in there or whatnot—and began feeling really grateful for the spaces presence and availability in my life. It was a retreat from the daily urban ‘hustle and bustle’ I was so accustomed to.

Where did the idea for your project come from?

I distinctly remember reading Studs Terkel’s Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do. This book remains in my memory not only because I found it to be fantastic, but because of the Bertolt Brecht quote included in the preface:

“Who built the seven towers of Thebes?

The books are filled with the names of kings.

Was it kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone? . . .

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go? . . .”

This quote captured the thoughts that had long been stirring in my mind, and is used in the introduction of my research, Garden Memories: Oral Histories of Urban Community Gardens in New York City. The works of Studs Terkel, and New York City’s urban gardening community at large, inspired my project. The project aims to investigate the experiences of urban community gardeners in New York City. I was interested in capturing the voices behind the movement.

Do you have a favorite story or moment from your interviews?

I really enjoyed working on this project. I met amazing and generous individuals, who openly shared their stores, and for that, I am endlessly grateful. I think one of the most moving moments from my interviews was during a discussion with Haja Worley:

“We had a group of young boys from the neighborhood who would come in and do work in the garden. They worked harder than the adults did, and I would give them a little stipend, you know. The thing was to encourage them, and they would come to work almost every day. They would come to the door and say, you know, like, “are we going to the garden today?” Or they see me in the street, “are we going to the garden today?” At the time, there were dealers in the community and we wanted them to know they didn’t have to idolize these drug dealers . . . they would identify with that and wanted to emulate that without knowing the consequences. They were always willing to come and work.”

In this moment, I felt both sad and proud. From first hand experience as a New Yorker, and an American at that, I understand the realness, per se, of the phenomenon Haja is explaining, which is saddening. However, on the other hand, I felt so proud to be talking with a local community member who has taken action and generated change in lives of neighborhood children.

Why do you think it is important to preserve stories of gardens and gardening?

I feel it is important to work across disciplines to tell stories, help assign meaning to events in relation to memory, and preserve knowledge. As a feminist, I aim to interview people around their own subjectivity, exploring time itself, because, to me, that is worth something. I believe in the power of the individual narrative, and the pursuit of attempting to understand a collective history. These gardeners and gardens have, to a degree, shaped New York City’s history, and their voices and stories should not remain unheard. It’s important to preserve these stories so that we can understand how these gardens have come to exist, and what they mean to community members. In doing so, we are tracing the process of becoming.

Read Eggimann’s interviews from Garden Memories: Oral Histories of Urban Community Gardens in New York City:

- The Joseph Daniel Wilson Memorial Garden

- The William A. Harris Garden

- Albert’s Garden

- LaGuardia Corner Gardens

We rely on storytellers like YOU (both professional and newbies!) to contribute the interviews and memories that make up the fabric of the Community of Gardens digital archive. We’re truly a community of storytellers, and this is a homegrown archive.

Do gardens tell a story about your neighborhood? Anyone can share a story! Get started with our gardener oral history interview guide, or share your story at communityofgardens.si.edu. Help us preserve stories of gardens, and the gardeners who make them grow.

-Kate Fox, museum educator

October 12, 2018 at 7:45 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

Back to School with Community of Gardens

The phrase “back to school” conjures up the crisp scent of falling leaves, the feel of a heavy backpack laden with textbooks . . . and the taste of juicy, late season tomatoes? School gardens have a long history in the United States, from their beginnings in the Progressive era to Victory Gardens during the World Wars, to the raised beds and outdoor classrooms found across schoolyards today. School gardens provide students with access to healthy and fresh food and the space to spend time outside learning about science, history, and everything in between.

School garden show hosted by the Summit Garden Club, New Jersey, circa 1900-1920. Hand-colored glass lantern slide, Archives of American Gardens.

As young people across the country head back to the classroom (if they haven’t already), here are a few school garden stories from our Community of Gardens digital archive to inspire teachers and students alike to find time to dig in the dirt and perhaps plant a seed or two this school year:

The Gardens at Chewonki in Wiscasset, Maine.

High school students, staff, and faculty tend the campus gardens and a saltwater farm with chickens, sheep, and a draft horse at this environmental organization on the coast of Maine. The farm produces 15,000 pounds of organic food each year.

Thomas Jefferson Middle School Garden in Arlington, Virginia.

The Thomas Jefferson Middle School Garden

This Virginia school garden (right in our own backyard in the Washington, D.C. metro area!) was created by a local Girl Scout troop in 2012. Today it is a community resource, playing host to classes and community events, and a portion of the produce supports the Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC).

The Spartan Garden at White Station High School in Memphis, Tennessee.

The Spartan Garden at White Station High School

A committed group of high school students in Memphis built their school garden from the ground up, raising money, negotiating with school administrators for space, and building raised beds, an herb garden, and an outdoor seating area.

Teachers, grow your curriculum toolkit with these online resources from Smithsonian Gardens for learning about—and celebrating—gardens this school year:

- Grown from the Past: A Short History of Community Gardening in the United States: an online exhibit from Community of Gardens with present-day and historical images.

- Cultivating America’s Gardens: the online version of the physical exhibit now on view at the National Museum of American History, a collaboration between Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Smithsonian Gardens, and the Archives of American Gardens.

- Smithsonian Gardens Green Ambassador Garden Design Challenge: Build your own school garden or greenspace with our handy guide, and become a Smithsonian Gardens Green Ambassador.

- Community of Gardens: Does your school or club already have a school garden? Share your story with the Smithsonian Institution by contributing your story to the Community of Gardens digital archive.

-Kate Fox, Smithsonian Gardens educator

September 5, 2017 at 8:00 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

Gardening for Good—Part I

Many of the stories in our Community of Gardens digital archive highlight the powerful impact gardening is having on urban, suburban, and rural areas around the country. Community gardening first gained popularity in the United States in the 1890s (read up on this fascinating topic in our online exhibit). For over a century community garden organizations have helped citizens learn to grow their own food, beautify their neighborhoods, and use gardens as a springboard for education and creating connections between neighbors. Right here in our own backyard in the nation’s capital, Common Good City Farm is growing fresh produce for their neighbors and teaching urban agriculture skills. And the Neighborhood Farm Initiative is teaching novice gardeners how to start and tend their own community garden plot through their Kitchen Garden Education Program. Gardens are proving to be key to providing access to fresh, healthy food in communities across the nation. Community of Gardens not only celebrates the hard work of gardening communities, but is also preserving the individual stories that make up this larger movement for future generations of gardeners and historians.

The Neighborhood Farm Initiative in Washington, D.C. offers gardening workshops for adults and families, teaching them how to plan, tend, and harvest a garden plot in their community garden.

Further afield, Grow Appalachia at Berea College in Berea, Kentucky partners with communities in six different states in the Appalachian region to provide garden grants, healthy summer meals for children in their community, and education and technical expertise for farmers and gardeners.

We recently received three stories about Grow Appalachia gardeners from Alix Burke, a AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer with the organization. She has spent almost a year collecting stories and images of gardens and gardeners in the program. The stories, ranging from a retired couple perfecting their home gardening skills to a flower farm managed by survivors of domestic abuse, are part of a verdant quilt of gardens doing good growing across the United States.

Married couple Della and Charles pose with the bounty of the harvest from their garden. They grew green beans, sweet potatoes, squash, and more. The couple expanded their home garden through the help of Grow Applaachia workshops.

Asked the importance of her work, Burke stated, “It’s important to collect these stories about Grow Appalachia gardeners and their gardens because it captures the lived realities of the program . . . from families bonding in the garden with healthier eating and exercise habits to people who are out of work turning to market gardening as a way to feed their families, both with the food they grow and with income they generate, the people and their gardens are, and always have been, the heart of Grow Appalachia.”

A flower grown on the Greenhouse 17 flower farm. With support from Grow Appalachia, Greenhouse 17 helps domestic abuse survivors get back on their feet and learn new job skills in horticulture and retail.

Stories about gardens can tell us about where we’ve been, and where we are going. The values and beliefs we hold, scientific innovation, foodways, and even economic trends are reflected back at us in the why and how of our gardens. What has Burke learned from her months in the field speaking to gardeners and learning about their experiences? “No one person’s experience captures what it’s like to be a Grow Appalachia gardener, but everyone’s story, in some way, contributes to the larger narrative of food security and the growing local foods economy in the region, ” she says. “Stories have always been important to the Appalachian region, from oral histories, to bluegrass lyrics, to the memories passed down with shared heirloom bean varieties. These interviews allow folks to continue a longstanding Appalachian tradition of speaking their own truths about their own lives, from the food they grow to the connections they make along the way.”

Are there gardens and gardeners doing good in your area? Encourage them to share their story with Community of Gardens! Get started here or email us at communityofgardens@si.edu.

-Kate Fox, Smithsonian Gardens educator

Growing a Digital Garden Archive

The gardens at the Chewonki Foundation in Wiscasset, Maine evolved over a century as the summer camp transformed into a year-round environmental education organization. Generations of students and staff have left their mark on the farm and gardens.

We are a nation of gardeners. Thomas Jefferson grew over 300 varieties of plants at his Monticello home and like any dedicated gardener kept meticulous records detailing the triumphs (and failures) of his adventures in gardening. In the nineteenth century Italian immigrants introduced new vegetables like artichokes to the United States. Today, heirloom seeds originating from around the globe—or grandma’s backyard—can be purchased online and grown wherever we make a home. The Smithsonian Gardens Victory Garden at the National Museum of American History tells a story of citizens feeding their communities during wartime years, as well as a story of the diverse cultures that comprise the American people. In the summer ‘Carolina Gold’ rice, a traditional crop from the Carolina Lowcountry, can be found growing only a few feet from ‘Corbaci’ sweet peppers, a hard-to-find heirloom from Turkey.

Inspired by the quote “you must be the change you wish to see in the world,” the artists of the S.A.G.E. Coalition in Trenton, New Jersey transformed an abandoned lot into a vibrant community garden and gathering space.

April is National Garden Month, and we are celebrating the diversity of American gardens and the gardeners who make them grow. Small gardens and large gardens, community gardens and backyards, our diverse stories are part of a verdant quilt of gardens growing across the country. Gardens tell us where we’ve been, and where we are going. They can tell us stories about how people in our communities lived in the past and articulate our cultural values in the present. So often our everyday stories—the dahlias bred by a great-uncle, the nursery owned by a family for generations, the hot peppers grown as a reminder of a faraway island childhood—are lost to the historical record, and therefore lost to future generations.

Community of Gardens is a participatory digital archive collecting stories from the public about gardens and gardening in America.

Community of Gardens is our answer to the call to preserve our vernacular garden heritage. Community of Gardens is a digital archive hosted by Smithsonian Gardens, in partnership with our Archives of American Gardens, and created by YOU. It is a participatory archive that enriches and adds diversity to the history of gardening in the United States and encourages engagement with gardens on a local, community level. The website uses a multimedia platform that supports images, text, audio, and video. Visitors can add their own story to the digital archive, or explore personal stories of gardens from around the country.

To contribute a story to the digital archive visit the “Share a Story” page on the Community of Gardens website to sign up for an account. Once you have set up your account you may then add a written story and photographs. If you’d like to add video or audio files to your story email them to communityofgardens@si.edu. You will hear from a Smithsonian Gardens education staff member within a few days, and your story will be posted on the website usually within 3-5 business days. Once you have shared a story, share another story, or encourage your friends and neighbors to do the same!

Paul, on the right, shared his family’s garden history with Community of Gardens, beginning with his great-grandfather immigrating to America in 1881. His grandfather Harry Sr., on the left, grew tomatoes, and today Paul maintains a large garden that he tends with his children.

We are looking for any story about gardens and gardening in America—even stories of Americans gardening abroad. Here is just a sampling of the stories we are looking to include in Community of Gardens:

- What’s growing in your own backyard, or on your apartment balcony? What motivates you to garden and how did you get your start? How does gardening enrich your everyday life?

- Interview a neighbor or family member about their garden.

- Memories of gardens past. Do you have strong memories of your grandparents’ garden, or visiting a public garden that no longer exists? Gardens can live on in stories and images through the archive.

- Family history. This is a good opportunity to get out the photo albums and scan old family photographs. Are you a fourth-generation gardener like Paul, pictured above?

- Community gardens—past and present.

- Did you immigrate to the United States from another country? How do your traditions and culture play a role in your garden?

- College and university gardens.

- School gardens. Involve your students in telling the story of their garden!

- Pollinator gardens and beekeeping.

- Americans gardening abroad. Are you a veteran or member of the Foreign Service? Did you keep a garden while living abroad? How did living in another country influence your garden?

- Sustainability and eco-friendly gardening.

- Stories of gardens committed to providing food access in urban areas.

Join us in preserving our national garden heritage—this month and every month. What is your garden story?

-Kate Fox, Smithsonian Gardens educator

April 15, 2015 at 8:42 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

Gardens All Their Own: Early African American Gardens in Detroit

Detroit was still a burgeoning industrial center in 1918 when John and Elizabeth Crews ended a journey “through six states seeking a home” and settled in the city. As part of the Great Migration, when African Americans began moving to Detroit in large numbers for employment opportunities and an escape from Jim Crow segregation, the Crews and many others were faced with the challenge of making a place and building community in a new environment.

In Detroit, many stopped their traditional gardening and food growing practices because urban-industrial life offered new opportunities to escape toiling on the land. Others changed and adapted their horticultural practices. Although the East Side of the city where many migrants first lived was quite dense, some managed to cultivate gardens here, while others moved to areas with more space.

Although photographed in 1949, this house with a small garden in Detroit’s East Side neighborhood suggests some of the ways Detroit’s African American migrants in the early 20th century made use of their yards. The image was taken by the agency charged with documenting and appraising the neighborhood before it was demolished to build Interstate 75.

Image Courtesy of Corporation Counsel – Real Estate Division records, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. Used with permission.

For those with financial means, the West Side of the city offered one of the first opportunities for African Americans in the area to cultivate a suburban garden aesthetic in a neighborhood of mostly single-family homes. Yards were landscaped with lawns and adorned with flowers and trees (often fruit trees). One resident planted so many flowers along her fence that she was known as “The Flower Girl.” Unlike other suburbs, however, rock gardens were often a common feature, especially in the more private space of the backyard. As one resident remembered, “Roosevelt was a serene and beautiful street with trees, green grass, butterflies, [and] beautiful rock gardens in back yards…” The neighborhood was so closely knit one resident described it as “village.” Home ownership created a shared sense of community as residents worked to maintain a suburban sense of place.

This rock garden in a back yard on Roosevelt Street was created from rocks the owners collected on their travels. From “Remembering Detroit’s Old Westside: 1920-1950,” 1997.

In the Eight Mile-Wyoming area, where the Crews lived, residents often had a different vision of the suburban ideal, raising chickens and growing gardens that often included vegetables, such the “Kentucky Wonder” green beans the Crews canned to eat throughout the winter. Corn was also a common sight in the neighborhood, along with an informal system of community gardening. As one resident told a visitor, they had no trouble with people stealing from their garden because, “we just plant a little more than we need each year to take care of that.” Alternately, “if we run low, we just get a few [ears of corn] off of somebody else’s. We all know that. We don’t care. We’re friends out here!”

A house with a cornfield in the Eight Mile/Wyoming neighborhood. Photograph by John Vachon, U.S. Farm Security Administration (courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division).

Not everyone found this more rural way of life appealing, however. During the 1920s and 30s, the Detroit Urban League (an organization founded to assist African American migrants in Detroit) often sponsored flower garden contests (complete with prizes of cash or flower bouquets) in this neighborhood to beautify what they considered to be unsightly “yards,” not gardens. According to one observer, during the spring contest houses in the neighborhood were “surrounded by riots of bloom…porches and fences sag under the weight of rambler roses, honeysuckle, and clematis; the yards bloom with myriads of flowers.”

While images of these gardens are sparse, bits and pieces from the written record help to illuminate the ways African Americans used gardens to create a sense of place, belonging, and community in Detroit, a tradition that continues with community gardening projects in the city today.

-Joe Cialdella, Enid A. Haupt Fellow

Sunflowers at the Manistique Community Garden, on Detroit’s East Side, August 2012. Photograph by Joe Cialdella.

February 12, 2013 at 8:00 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

Reflections on Landscapes, Archives, and History Part I

Back in the warmer days of August, I had the opportunity to attend the Detroit Agriculture Network’s 15th Annual urban garden tour in Detroit, Michigan. Hundreds of people gathered in the late afternoon at Eastern Market to board buses or take off on bikes to visit gardens and hear from gardeners on the east, west, and central areas of the city. Above all, it was an occasion to hear from passionate individuals and view the city from the ground up.

A garden tour stop at Manistique Community Garden on Detroit’s East Side

Image by Joe Cialdella

Even though my first experience seeing and volunteering with urban gardens in Detroit was in 2004, looking at the gardens in Detroit’s landscape – a compelling assortment of open space, roads, and buildings (many still inhabited and, yes, many long abandoned) – continues to be at once jarring and inspiring; a poignant and thought-provoking place because of the layers of time and meanings collected here. As garden historian Kenneth Helphand writes,

“When we see an improbable garden, we experience a shock of recognition of the garden’s form and elements, but also a renewed appreciation of the garden’s transformative power to beautify, comfort, and convey meaning despite the incongruity of its surroundings. Gardens are defined by their context, and perhaps the further the context from our expectations, the deeper the meaning the garden holds for us.”[1]

As a historian, the context I look to when I see these gardens is often that of the past. How did social, political, economic, environmental and cultural conditions shape transform these spaces? The seeming improbability of gardens as a part of post-industrial landscape challenged my expectations, and sparked my interest in learning what deeper meanings, and histories, gardening in Detroit might have.

Through this experience with a place, the landscape itself becomes an inspiration and an archive. A record of changing tastes, values, style, and use, for example, is captured by looking closely at the location, age, and size of buildings. Natural features, such as rivers and waterways often mark the original contribution to the archive of a landscape.

Yet in a place like Detroit, where seemingly endless redevelopment and decline are starkly juxtaposed, you cannot help but wonder what is missing from the landscape today. This can be particularly problematic when digging deeper into the history of such fleeting spaces as small scale community-minded gardens in a constantly changing urban environment.

Old and new features of the landscape meet where the Greening of Detroit’s “Detroit Market Garden” borders an industrial building.

Image by Joe Cialdella

Gone from Detroit’s landscape is the rich tradition of gardening culture that came before the contemporary movement. For example, during the 1890s, Mayor Hazen S. Pingree started a municipally-supported gardening plan to feed unemployed workers (many of whom were Polish and German immigrants). The Garden Club of Michigan was one of the 12 founding members of the Garden Club of America in 1913. During the Great Migration, African Americans moving to Detroit used gardens as a means of providing food and improving the appearance and value of their neighborhoods. And in the 1930s, thrift gardens again provided sustenance to many of those left unemployed by the Great Depression.

As the Haupt Fellow at Smithsonian Gardens, I’m in the process of digging up the details of these gardens using more traditional archives to better understand the history of what it means for people to contribute to an urban-industrial landscape by gardening. This can be a difficult task since the spaces themselves are often fleeting and records of them scarce, unlike many of the design plans and photographs of more famous landscapes. Looking back to the 19th and early 20th centuries, sociological surveys, government reports, meeting minutes, scrapbooks, maps, newspapers, magazines, and photographs are often surprisingly detailed documents that provide us with a way to re-imagine what these types of gardens looked like, their contexts, and how they were used in the past.

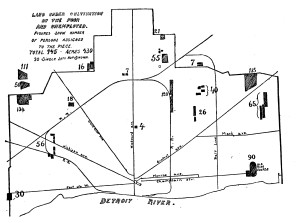

Map of “Pingree’s Potato Patches” from an 1894 government report

Together, the actual landscape and the two-dimensional records of experiences long removed from the land lend themselves to a fuller garden history that contributes not only to understanding gardens themselves, but also how gardens can reflect changing social, political, economic, environmental, and cultural contexts that give more people a way to consider the role of gardens and landscapes in their own lives.

The fleeting, seasonal nature of gardens also points to the importance of documenting garden spaces today. While we all hope they will last forever, proactively considering how you can preserve a garden or landscape’s history for your family, community, or organization provides an opportunity for reflection and sharing of information between one another that can often help to create connections and networks of support that will help these spaces exist into the future. One way of doing this is through creating a collection of photographs, such as those found in Smithsonian Gardens’ Archives of American Gardens. Look for more on this in my next post.

Tomato Plants and Detroit’s Skyline.

Image by Joe Cialdella

– Joe Cialdella, Haupt Fellow, Smithsonian Gardens

For more information on being a part of preserving garden history or beginning your own research, check out the resources below.

Take 10 minutes to “tag” an image form the Archives of American Gardens to help make their extensive collections more accessible to the public, researchers, and landscape designers!

These websites offer good tips and instructions for beginning your own archival adventure into the history of a garden or landscape near you:

http://www.williamcronon.net/researching/landscapes.htm

http://envhist.wisc.edu/cool_stuff/landscapetips.shtml

http://www.ultimatehistoryproject.com/early-detection.html

[1] Kenneth Helphand. Defiant Gardens: Making Gardens in Wartime, 2006, pg. 9.