Posts tagged ‘Victorian’

Botanical Scrapbooks

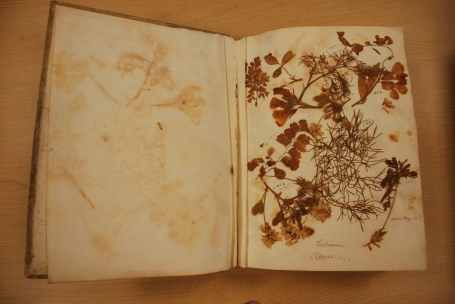

Collecting and preserving plants has always been a popular pastime, especially in the 19th century. Both men and women pressed flowers and foliates (leaves) to keep in botanical scrapbooks. This activity served a variety of interests, both scientific and sentimental.

Whatever their purpose, plants that were collected were prepared and added to scrapbooks in a similar fashion. Flowers typically were pressed in between the pages of a book by the amateur hobbyist while the more serious collector often used a field press. The field press was superior because of its ability to preserve a plant’s color and create a more precise specimen. Field presses were composed of two boards of wood, leather straps and sheets of blotting paper. The process was simple: a plant or flower would be placed between two pieces of paper, then placed between boards. Leather straps would be tightly wrapped around the packet and firmly secured. When sufficiently dry, the specimen would be removed from the field press and glued, sewn, or attached with thin gummed strips to a scrapbook page.

The way in which these items were displayed depended on the type of book the collector wanted to create. Scrapbooks for botanical study usually included a taxonomic description (family, genus and species), a physical description of the plant as well as the date and location of when and where it was collected. Scrapbooks created for sentimental reasons might have been created as a craft project or to serve as a memento in remembrance of a person, event or place.

The Smithsonian Gardens’ Garden Furnishings and Horticultural Artifact Collection includes three examples of 19th and early 20th century botanical scrapbooks.

Scrapbook as Herbarium for Botanical Study

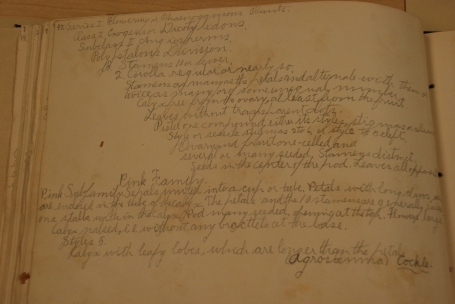

A botanical scrapbook (FJP.1987.364) dated 1905 was created by Margaret May Hill and is an example of an herbarium or collection of dried flowers that are labeled and described for botanical study.

Handwritten taxonomic and physical description of pressed pinks on opposite page.

Botanical Scrapbook as Memento

The botanical scrapbook titled “Flowers of Remembrance” is a sentimental travel log of visits to sites all over Italy during the 1850s. Instead of a travel journal with written entries, the pages are filled with flowers and plants collected from various sites as mementos. One page shows pressed flowers collected at the Roman Coliseum in 1853, 1854 and 1856 all on the same page.

Botanical Scrapbook for Study and as Memento

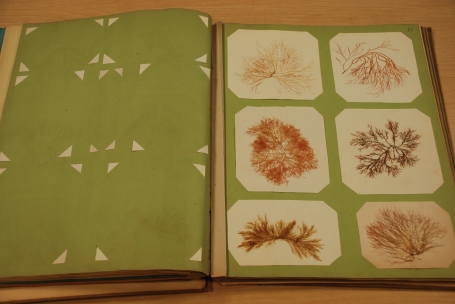

A book of dried water ferns (Salviniales) is both scientific and sentimental as it illustrates both the incredible variety and beauty of water ferns. The front of the book reveals that it was a gift from a grandmother to her grandson (Hester Schell to Howard Schell) on November 11, 1900.

For further Reading:

Puckett, Sandy. Fragile Beauty: The Victorian Art of Pressed Flowers. New York: Warner Books, Inc., 1992

Whittingham, Sarah. The Victorian Fern Craze. Oxford: Shire Publications Ltd., 2009.

–Janie R. Askew

Research Assistant, Smithsonian Gardens

MA Candidate, History of Decorative Arts

The Smithsonian Associates – George Mason University

Rustic Ornament in the Victorian Garden

This Stump Pedestal is an example of a popular Rustic Style of garden ornament that developed in the late nineteenth century. This style was adapted to the garden from the Romantic Movement, which was characterized by its nostalgic look at nature. Its love of picturesque landscapes was recreated in the garden. The “English Landscape Garden” or “Jardin Anglaise” relied on objects in the rustic style to create an informal setting that put an emphasis on the true nature of the land.

1979.26, Pedestal, Rustic Stump, late 19th C, Cast-iron, paint, 22 x 18 x 13.

These gardens were more sparsely ornamented than other garden styles. Objects were often created using materials found in nature such as tree branches, twigs, roots, bark, pinecones, animal horns, antlers and seashells and were often handmade. Cast-iron, already a popular material used in the garden used molds that would mimic these natural assemblages. As we see in the rustic stump pedestal, it is cast in a high relief and mimics the look of a tree trunk with thick bark that is entangled roots and oak leaves. It would have been used as a base for a plant stand or bird bath and occasionally could have been used a planter itself. These objects were usually painted in white, black, or natural colors that would blend in with the landscape.

Horticulture magazines and other serials provided layout, planting, ornament and structure designs that would have incorporated objects such as the stump pedestal. This was a popular item that can be seen in the 1858, Janes, Beebe, & Co. New York trade catalogue, the 1875, Coalbrookdale Company of England trade catalogue, and the 1893, J.W. Fiske Iron Works trade catalogue.

Many of these rustic style cast-iron ornaments have been broken or damaged. However, gardeners still feature them in their landscapes today. Using the broken pieces and fragments of these antique garden furnishings, they create interesting displays that incorporate the past and create a nostalgic and picturesque setting for the present.

Further Reading:

Israel, Barbara. Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999.

Himmelheber, Georg. Cast-iron Furniture, and all other forms of iron furniture. London: Philip Wilson Publishers Ltd, 1996

Hill, May Brawley. Furnishing the Old-Fashioned Garden: Three Centuries of American Summerhouses, Dovecots, Pergolas, Privies, Fences & Birdhouses. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1998.

-Janie R. Askew

Research Assistant, Smithsonian Gardens

MA Candidate, History of Decorative Arts

The Smithsonian Associates/George Mason University

Victorian Love of Nature, Ornament and Decoration on Display

OH.1985.32, Plant Stand, c. 1850-1900, Cast-iron, 44” x 25.5”

Plant stands such as this, from the Smithsonian Gardens’ Garden Furnishings and Horticultural Artifacts Collection, were the perfect tool to combine a love of nature with a taste for ornament and decoration in the Victorian Era. Named for Queen Victoria of Great Britain, the Victorian Era classifies the period of society and the fine and applied arts during her reign from 1837 to 1901.The cultivation of plants was a widely popular pastime for the Victorians in all levels of society, and their toils were proudly displayed in homes and gardens. Plant stands became an essential item for the exhibit and storage of flowers and foliage. Their practical and decorative benefits were amplified by the link they provided between the domestic interior and the natural world that had gone missing due to the Industrial Revolution.

Plant stands were manufactured in England, America, and France, and came in a variety of forms and materials. Cast- and wrought-iron were the most common materials for garden ornaments such as this; however, they also came in wood, wicker, glass, and ceramic versions and were usually painted white, black, brown, or green. Circular, semi-circular, or squared structures could be positioned against a wall or in the center of a space. Single level and tiered versions were popular, in addition to the plant stand we see here that has multiple appendages.

This type of plant stand was made using separately cast arms attached to a central axis rod. The arms could be rotated and moved vertically along the pole to display plant specimens of various sizes. The cup at the end of each arm would hold a small flower or foliate, which were often in their own removable liner so they could be changed out seasonally.

Plant stands are still a popular indoor and outdoor garden accessory for displaying plants. Just as they did during the Victorian Era, they showcase a selection of seasonal varieties to beautify the home and bring nature within reach.

Further Reading:

Israel, Barbara. Antique Garden Ornament: Two Centuries of American Taste. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999.

–Janie R Askew

Research Assistant, Smithsonian Gardens

MA Candidate, History of Decorative Arts

The Smithsonian Associates/George Mason University

Roses are red, Violets are blue: What are these flowers saying to you?

Walcott, Mary Vaux. Pink Rose with Violet, watercolor on paper, 1876. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

Sugar is sweet.

And so are you.”

The sweet and playful lyrics of this poem are found among the nursery rhymes of Mother Goose and often make their way into the sentiments of Valentine’s Day cards.

Is there more to this sweet refrain? Attaching meaning to certain flowers has occurred throughout history, but during the Victorian era the ‘language of flowers’ was turned into a studied exercise. This was a code that attached characteristics and expressions to all types of flora. Entire dictionaries were also published to pair each flower and its color to a specific meaning.

When we consider the verse again using the language of flowers as our guide, the words of the familiar poem have a renewed sense of purpose.

Roses are red: The meaning of roses varies according to their color; the red rose is one of the flowers most associated with Valentine’s Day because of its connotations of love, passion, desire, and beauty. To give a red rose is to say, “I love you.”

Violets are blue: Though we see violets used less frequently than roses in a valentine bouquet, they are forever associated with one another in these verses. Meanings of modesty, faithfulness, humility, and simplicity are embodied in the delicate violet, and it holds the answer to the bold statement of the red rose. To give a violet is to reply, “I return your love.”

Reconsidering this simple rhyme with the meaning of the red rose and its companion the blue violet, the words and the flowers they invoke reinvigorate the quaint nursery rhyme, and reveal truly romantic sentiments to be combined in the perfect bouquet on Valentine’s Day.

-Janie R. Askew

Research Assistant, Smithsonian Gardens

MA Candidate, History of Decorative ArtsThe Smithsonian Associates – George Mason University

It’s Not Just About Plants

Gothic Settee, Kramer Brothers Foundry Company, circa 1880-1900. Garden Furnishings Collection, Smithsonian Gardens.

In 1973, just a year after it was established, Smithsonian Gardens acquired its first antique garden furnishing for display on the Smithsonian campus in Washington, D.C. Since then, over 2,000 garden furnishings and horticultural artifacts have been collected by Smithsonian Gardens ranging from delicate bouquet holders to towering fountains. While most of the pieces date from the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, all help to document important facets of our garden heritage.

The Garden Furnishings Collection includes hundreds of cast iron pieces such as settees, chairs, urns and wickets. Dozens of these furnishings are currently on display throughout a number of the Smithsonian gardens. They are a particularly appropriate complement to the ornate architecture of the Smithsonian Castle and the Arts and Industries Building.

While not much is known about the origins of many specific pieces in the collection, Smithsonian Gardens staff and interns have gleaned general information about some cast iron furnishings from historic trade catalogs that document the wares of numerous foundries operating in the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Fortunately, one settee on display in the Ripley Garden features a maker’s mark that indicates where it was manufactured and by whom.

With the rise of the middle class in the mid-nineteenth century, many objects made for utilitarian use, such as garden furnishings, saw a dramatic change in the way they were designed and manufactured. Victorian furniture is characterized by a jumbling of styles, often incorporating design elements from previous eras, from High Renaissance to Gothic to Rococo. Makers and buyers would simply pick elements they found pleasing and incorporate them into a piece with no regard to purity of the original designs.

For example, this Smithsonian Gardens’ settee incorporates both Gothic and Rococo design elements at the same time, something that would hardly have ever been done prior to the Victorian era (1837-1901). Overall, the settee is extremely Rococo in its form and design. Characteristics of the Rococo period can be seen in the fluid curl of the cabriole legs and in the “c” scrolls that make up the arms. These two elements are characteristic of the asymmetry and playfulness of the Rococo period of the late 18th century, and would not have been combined with the structure and orderliness favored during the Gothic period (12th-16th centuries).

Interestingly, this settee features more Rococo elements in its design than it does Gothic, which was the name given to the pattern by the manufacturer, the Kramer Brothers Foundry Company of Dayton, Ohio. The only distinctly Gothic element is the back of the settee, which is comprised of four rows of repeating arches. It is this combination of characteristics from different styles that makes this piece unique and interesting, much like countless other objects from the late Victorian period. In pieces like this settee, it is easy to see why the period—which was overwhelmingly influenced by the large variety of revival styles—has been called Victorian Eclecticism.

-Brittany Spencer-King, Research Assistant

January 30, 2013 at 9:00 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment

Over Sea and Land … and into the Victorian Parlor

OH.GF.1980.11, Wardian case – Miniature Church, 20th century, Wood, Glass, 27” x 16.5” x 12.5”

Often referred to as the Victorian Era, the nineteenth century was characterized by a growing interest in the collection, preservation, and identification of botanical specimens. New species of plants were carefully imported to England and America from all over the world, and cultivation of these exotics became a popular pastime. This interest was not met without challenges. The soot and pollution from the factories of the Industrial Revolution made it difficult for new plant species to survive. A London surgeon and amateur naturalist, Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward (1791-1868) stumbled upon a solution one day when he noticed that a bulb he had moved to a glass jar, and then forgotten, was thriving in this little habitat. Soon after this discovery, he began making ‘closely glazed cases’ (sic) for growing and extending the life of plants. These glass plant cases, renamed Wardian cases in homage to their inventor, were like tiny greenhouses that were sealed but not airtight. They provided an atmosphere free of pollution with ample light, heat, and moisture ideal for the cultivation of exotics.

The invention of the Wardian case also allowed for new possibilities for transporting plants across long distances. Shipping during the nineteenth century is not what we know today: no priority mail or next-day air delivery options. Railroads, carriages and ships took weeks to deliver plants to a location. Inside a Wardian case the survival rate was considerably higher, as plants were able to travel in a protective environment that provided for their every need.

Despite contributions to the study of botany and improvements to the transportation of plants, the Wardian case is typically associated with household décor rather than invention. Their small size made them accessible to a larger portion of society who could not afford to own greenhouses. Because of their ability to preserve plants indoors, Wardian cases were brought into the parlors and drawing rooms of the Victorian household. This was in large part due to the encouragement of growing and tending to plants as a suitable hobby for young ladies. To suit the Victorian taste for decoration, cases were made to look like miniature buildings such as churches and famous houses. Comprised of a variety of materials that were suited to any price range, they were made in all shapes, sizes, and styles. Their popularity and availability made them a staple of fashionable drawing rooms.

This Wardian case in the Smithsonian Gardens’ Garden Furnishings and Horticultural Artifacts Collection is an example of a nineteenth century innovation and a characteristic feature of the Victorian-era domestic interior in both Britain and America.

Further Reading:

Allen, David Elliston. The Victorian Fern Craze: A History of Pteridomania. London: Hutchinson & Co, 1969.

Whittingham, Sarah. The Victorian Fern Craze. Oxford: Shire Publications Ltd., 2009.

–Janie R Askew

Research Assistant, Smithsonian Gardens

MA Candidate, History of Decorative Arts

The Smithsonian Associates/George Mason University

January 4, 2013 at 10:15 am smithsoniangardens Leave a comment